Earlier this month, I attended a brilliant presentation by Petra Alsoofy, the Outreach and Partnerships Manager from the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU). You may not be familiar with ISPU: it’s an organization based in Dearborn, Michigan, which was founded after the attacks of September 11, 2001. According to their website, “ISPU provides objective research and education about American Muslims to support well-informed dialogue and decision-making.”

ISPU seeks to help everyone understand more about what life is like for American Muslims. That was the emphasis of Petra Alsoofy’s presentation a few weeks ago. She shared lots of information with about fifty of us who gathered together at St. John’s Episcopal Church in Midland. (You can watch her presentation at this link; enter the passcode Xffx&8s9 and you’ll get access to it.)

After Petra’s presentation, I signed up for the ISPU email list. It’s important for me to hear perspectives that are outside my tradition. That’s why, among other things, I have listened to the podcast Inspired (by Interfaith Voices) every week for around fifteen years.

Yesterday, ISPU sent out results of a survey on what American Muslims believe about climate change. The title of the report reads like this: “The Majority of American Muslims Believe that Climate Change is the Result of Human Behavior and that Government Regulation is a Way to Solve for it.”

What I’m writing about today is “Why I’m Not an Evangelical.” I promise, these things are related to each other.

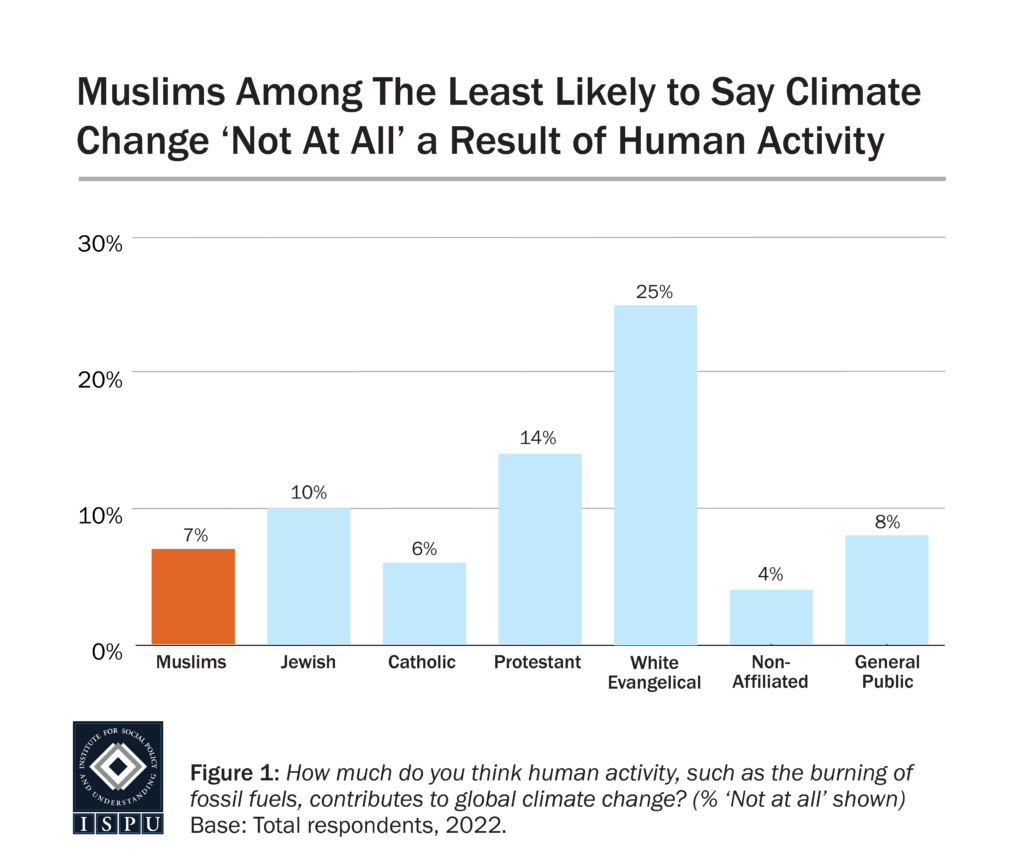

The ISPU surveyed a representative sample of Americans from all sorts of religious backgrounds: Muslim, Jewish, Catholic, Protestant, White Evangelical, Non-Affiliated. They asked all sorts of questions, not just about climate change. But one of the questions is striking:

“How much do you think human activity, such as the burning of fossil fuels, contributes to global climate change?”

Across the board, the percentage of respondents who answered “Not At All” was pretty low. The general public (average of all responses) came in at 8% saying “Not At All,” and almost all religious groups were within a few percentage points of that value.

Almost all. All of them, that is, except for two.

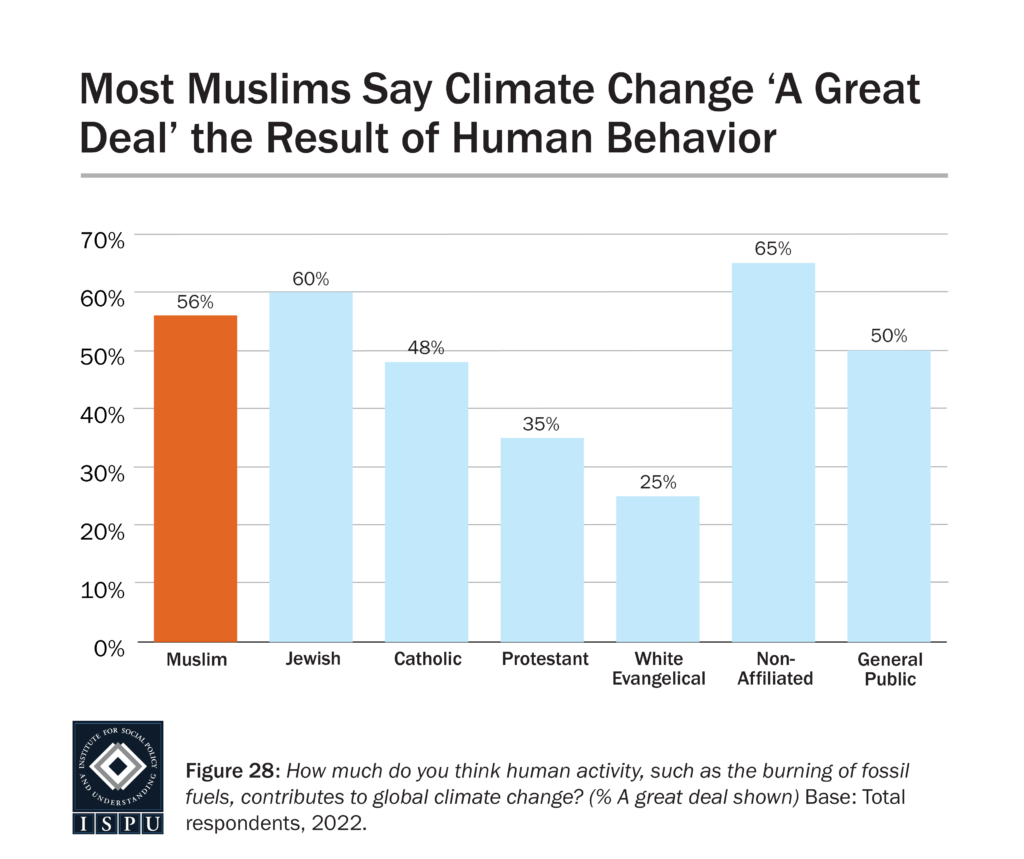

The percentage of respondents who answered “A Great Deal” was similarly pretty consistent. The general public average was 50%, and almost all religious groups clocked in at similar values: 56%, 60%, 48%, 65%.

Almost all. All of them, that is, except for two.

Take a guess which two religious groups, from those listed above, are the exceptions.

Protestants and White Evangelicals. In that latter group, fully 25% of them believe that humanity has no impact at all on climate change. The exact same percentage of them (25%) responded “A Great Deal” – that’s half of the national average.

Protestants and White Evangelicals. In that latter group, fully 25% of them believe that humanity has no impact at all on climate change. The exact same percentage of them (25%) responded “A Great Deal” – that’s half of the national average.

Protestants and White Evangelicals have their heads buried in the sand when it comes to humanity’s impact on climate change. No other religious group is like this. The general public is not like this. We (and I use that pronoun loosely) are outliers. For some reason, everyone else can believe that human activity (like burning fossil fuels) has something to do with climate change. But not us.

Why is that?

I could list a lot of reasons why. But none of those reasons have anything to do with religious beliefs. It is not because of religious beliefs that Protestants and White Evangelicals deny climate change. No, something else is going on here. There is nothing within Evangelical Christianity itself that proclaims, for instance, fossil fuels are good to burn.

Essentially, Evangelicalism has, over the past forty years or so, become deeply intertwined with a particular set of views on politics, economics, and all sorts of social issues. To say someone is an Evangelical (or even a Protestant) is, to an extent, to put them into a certain sociological category. Evangelicals vote Republican. Evangelicals are pro-life. Evangelicals are pro-coal and pro-gasoline and pro-low-taxes. Evangelicals are pro-Second-Amendment. Evangelicals are pro-prayer-in-schools. There are so many ways in which the definition of Evangelical Christianity has moved far beyond the boundaries of spirituality, religious traditions, and religious practices. Yes, there are some religious beliefs that support these sociological positions, but there are other valid religious beliefs held by other Christians who support very different positions.

It’s for this reason that I do not consider myself an Evangelical Christian. A Christian, yes. A pastor in a Christian tradition that tends to be more Evangelical than not, yes. A pastor who loves this tradition (Church of God, Anderson, Indiana) and believes that it has something important to offer the world, yes.

Part of what the Church of God offers is an emphasis on unity. Christians are united because of Jesus, the one whom we follow. We are not expected to be uniform in our stances on sociological and political issues. We are expected to do something much harder: to work toward unity with others even when we disagree with them. That means listening to them, hearing their perspectives, and being willing to change so that humanity can move forward together.

When I look at the two graphs shown above, I have a visceral, negative reaction. I don’t want to be associated with those outlier statistics. I want us to do better, for the sake of all humanity.

Climate change is just one issue. There are lots of others. We Evangelical Christians have a lot of thinking, listening, and growing ahead of us.