Perhaps you have seen the new series on Netflix called “The Queen’s Gambit.” That show brings back a lot of memories for me. More than two decades ago, I was a high school student, and one of my favorite extra-curricular activities was to play chess with our school’s chess club. We stayed after school one day each week to play, practice, study, sharpen our skills, and have a good time. Our practices were in preparation for weekend tournaments which were scattered throughout the school year.

Most of these tournaments were Saturday events. We would arrive at a school or convention center – local to us, across the state, or in another state – in the morning for registration. We then would play five games, each lasting up to ninety minutes. Then, at the very end, the tournament results would be announced, and trophies would be given to the top several players and teams. Everyone would celebrate a job well done, and we all would go home.

I was on a good team, and I was a pretty decent player. So we expected to win. At each tournament, our team expected to come home with a team trophy. We would easily finish in the top ten, but maybe we could place in the top five, or even win the whole tournament. Individually, I usually finished at least in the top 20. If I had a pretty good day, I would finish in the top 10. Finishing in the top 5 meant I had played really well that day – winning four out of my five matches and only losing once, maybe winning four games and drawing (tying) the fifth, maybe even winning all five.

We won a lot. We won the state team championship in my junior year. We were the sixth place team in the nation that same year. I brought home lots of trophies from smaller tournaments: second place here, ninth place there, fifth place here, seventh place there.

But I don’t want to write about winning today.

I want to write about losing.

I had a couple of bad days in my chess tournament career. Really bad days. Maybe I didn’t sleep well the night before, or maybe I just wasn’t mentally focused. In one tournament, out of five games, I went 1-3-1 – winning only one game, losing three, and drawing one. Needless to say, I didn’t bring home a trophy that day.

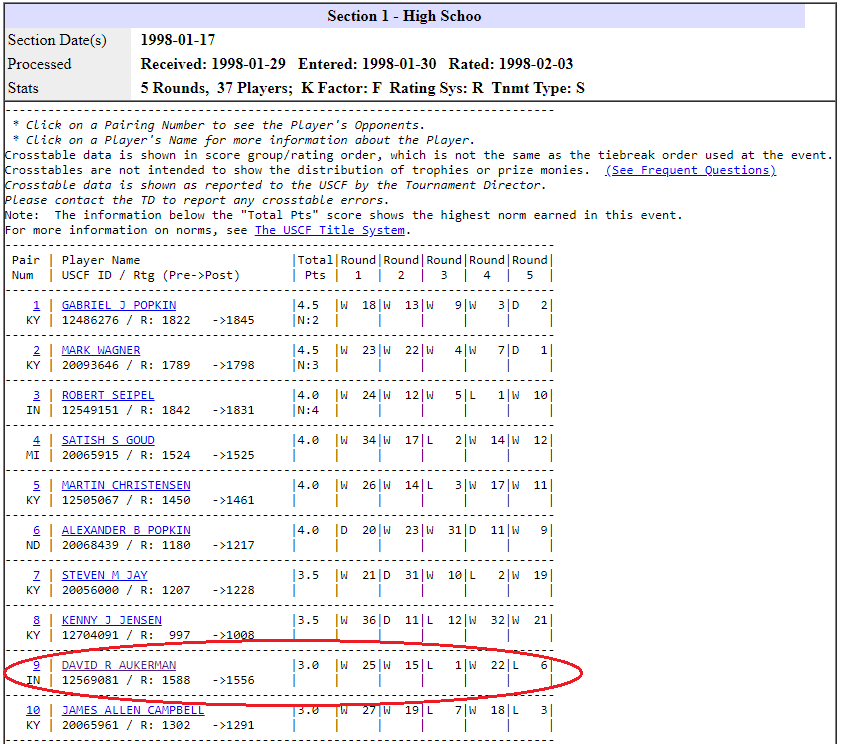

But the one day of losing that really stands out in my memory comes from my senior year in high school, twenty-three years ago this winter: the eleventh annual Lexington Winter Scholastic, in Kentucky, about four hours away from home. For some reason, my mom and I drove separately from the one teammate of mine who played in that tournament too. That was unusual because my parents rarely came to my tournaments. (I don’t blame them! What parent wants to sit in a high school cafeteria all day on a Saturday?)

In the five rounds of that tournament, I won three games and lost two.

My first loss came to a guy named Gabriel Popkin, who ended up winning the whole tournament. I lost to him in the third round, which didn’t bother me too much.

But then, in the fifth and final round, I faced his younger brother, Alexander Popkin. This kid was much younger – I think he was in middle school. His chess rating (a numeric measure of a player’s skill) was much lower than Gabriel’s, and much lower than mine. I fully expected to beat him and finish the day with four wins and the one loss.

Alexander wiped the floor with me. The game wasn’t even close. He won easily. And I still remember him sitting across the board from me, smirking at me, as if he were thinking, “My brother beat you, and now I’m beating you. You’re not that great!”

I lost badly. Not just on the chessboard – in real life, too. I left the gymnasium and started crying furious, angry tears because I had been so humiliated. My mother tried to console me. I remember another lady, a stranger, probably some other player’s mom, saying to me that it was honorable just to compete and participate in the tournament. I remember crying and shouting, “there’s no honor in this!”

I made quite a spectacle, I’m sure.

I was so upset that I asked my mom if we could leave right away. I didn’t want to be there any longer. I didn’t want to wait for the trophy presentation. I just wanted to go home.

So we left.

The next week, back at school, I found out from my teammate (who won four games and finished third) that I, with my three wins, finished ninth out of 37 players. The tiebreak system put me at the top of the list of players with three wins, because my two losses were against players who finished first and sixth.

I finished in ninth place. They awarded trophies to the top ten players. When they called my name, I wasn’t there. I was already on the road back home.

I was such a bad loser. To this day I don’t know exactly why losing to Alexander Popkin sent me over the edge, but it did. (It’s quite possible that I was exhibiting some early struggles with anxiety, which became a bigger issue for me in the next several years. Thankfully, through therapy and medication, I don’t have these kinds of outbursts any longer!)

I learned several important lessons about losing that day:

- Losing badly can overshadow any wins and any positive recognition by others.

- People notice when someone loses badly. (My mom, the other parents, the other players, my teammate…)

- Perception does not always correspond to reality. (I thought I did poorly; I actually finished ninth.)

- Losing is part of life.

- No one can win all the time.

- Running away doesn’t change the results.

- Losing tells us more about ourselves than winning does.

What can you learn about yourself through your experiences with losing? What can you learn about others by how they lose?